Fangio - 1954 Campeón del Mundo!

From success, you learn absolutely nothing. From failure and setbacks conclusions can be drawn.

The overwhelming Mercedes-Benz victory at the 1954 French Grand Prix had echoed around the world. A victorious return to the highest level of motorsport after a 15-year hiatus. To the casual observer it perhaps appeared inevitable. To those at Stuttgart it was anything but, and the success at Reims was a prelude to a challenging summer.

Development of the W196 Formula One car continued apace; not only issues needing addressed, but also weaknesses that quickly became apparent. Time was short, for even in a World Championship that only consisted of nine rounds, the races came thick and fast.

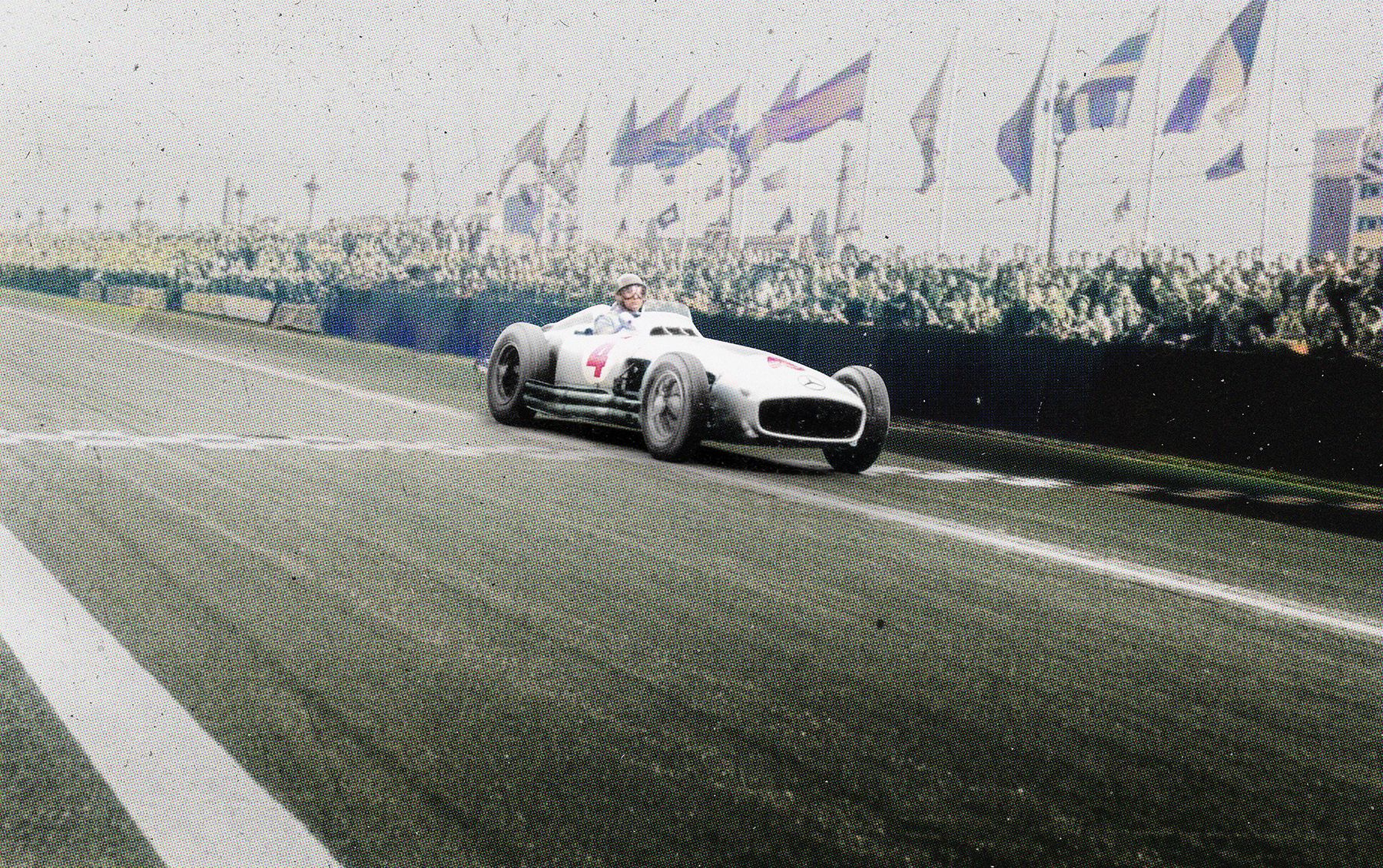

A fortnight after Reims, the British Grand Prix. A planned open-wheel, more conventional version of the W196 was not yet ready, but it wasn’t considered a huge issue for the race at Silverstone. The remaining niggles from Reims had been ironed out and two beautiful silver machines were presented, in all their streamlined glory, for Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling.

Rolled from the Daimler trucks in the paddock, diligently prepared, raced hard… and soundly beaten by Ferrari and Maserati.

In retrospect, Reims had played to the W196’s strengths – rather, it had not highlighted its weaknesses. Silverstone made it apparent that the car lacked grip in fast bends, in the dry and more so during the wet conclusion to the race.

At the time it was assumed that this was oversteer in nature, and that the root cause was likely the tyres. With the ‘300 SL’ racing car Mercedes had run a comparison test with Engelbert, Pirelli and Continental tyres. Pirelli clearly gave the best performance, but a suitable supply was unlikely to be forthcoming. Continental was chosen, given the past business and competition links between the two firms, and it was accepted that they too had a 15-year bridge to cross.

Nevertheless, as at Reims, Fangio took pole position at record speed - recording the first 100mph lap of Silverstone. But, forced to make up for a deficit in race pace, he worked the W196 hard – pushing beyond his innate mechanical sympathy to rev the motor to 9800 rpm. Trusting the desmodromic valve gear to save the machine from utter ruin. His Mercedes ultimately crossed the line in fourth place; dented from hitting the oil drums that marked track limits, and running on seven cylinders.

Ahead of Fangio, the winner for Ferrari was his compatriot Frolián González. González who had humbled the Alfettas at Silverstone in 1951 – derailing Mercedes’ plans for an earlier F1 debut. In second place was Mike Hawthorn – also on a Ferrari, and outspoken with his view of the Mercedes’ (under)performance. Third at the flag was another Argentine, the next generation, Onofre Marimón. Marimón was Fangio’s protégé, and son of Fangio’s great friend and pre-war team-mate, Domingo Marimón. That final podium place had been destined for Stirling Moss, until his Maserati failed him.

Needless to say, the next championship round, the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, was given the full focus of Mercedes’ attention. Earlier development testing of the W196 at the ‘Ring had proven less than spectacular, and after the trials of Silverstone it was clear that the new version of the car was urgently needed.

Four machines would be required for the German race, as Fangio and Kling were to be rejoined by Hans Herrmann and the great Mercedes pre-war champion, Hermann Lang. Lang was to make his Formula One debut, having previously raced a Maserati in a Formula Two round of the Drivers World Championship. More than a great racer, he was a talisman – a direct link to Mercedes’ last Grand Prix championship success.

W196 Reinvented

The work to present the new re-bodied, open-wheel W196 started immediately after the British Grand Prix with a two-day test at the Nürburgring. Kling and chief engineer Rudi Uhlenhaut taking turns to shakedown an interim design. Data crunched, the cars – with new bodywork and repositioned oil tanks – were produced and arrived at the ‘Ring on the second day of the Grand Prix race meeting. Fangio and Lang using a pair of streamliners to practice on Friday.

For Saturday qualifying Fangio finally got his hands on the new Mercedes W196, and promptly went faster than all the rest. Pole position, 9min 50.1sec. Eight seconds faster than Kling’s pre-Reims Nürburgring times. Proof perhaps that the earlier perception (hope) that, ‘fuel injection system and Fangio will make all OK’ was true.

Another machine pressing-on in qualifying was the Maserati 250F of Onofre Marimón. Onofre was besotted with the ‘Ring, and under pressure. With some factory support, Moss, on his private Maserati, had been showing great speed and producing impressive drives, even if results had eluded him. Now Moss was splitting the Mercedes in qualifying, and Marimón couldn’t come close, even with a full works 250F.

Onofre set out for one more flying lap; and that is when his mentor, Juan Fangio caught sight of him, around a third of the way into the lap.

“I watched Marimón from afar, pleased by his style. It seemed to me that I was sending him advice by telepathy and smiled to myself with satisfaction when I saw Pinocho [his nickname] do exactly what I should have done at the wheel of his Maserati.”

Downhill the pair raced, towards Wehrseifen.

“… I saw his machine suddenly go wild. Probably one of the wheels locked unexpectedly, but what I could see confused me.”

The Maserati slewed and smashed its way off the road. Punched through the scenery, into the void. Horrified, Fangio momentarily lifted, before realising that he would trigger a huge crash among the chasing cars. Returning to the pits he met González with the news: ’Pinocho’ Marimón was dead. The two rivals – deep in a championship battle, Ferrari versus Mercedes-Benz – united by grief. Fangio stunned to silence, the great González dissolving in his arms.

“I can’t drive any more. I’m finished,” Fangio whispered to Neubauer.

The Mercedes manager gave him some time, then made it clear that they had come too far together to turn back. There was much at stake – much yet to do.

The world turns, the sun rises, the cruel sport continues.

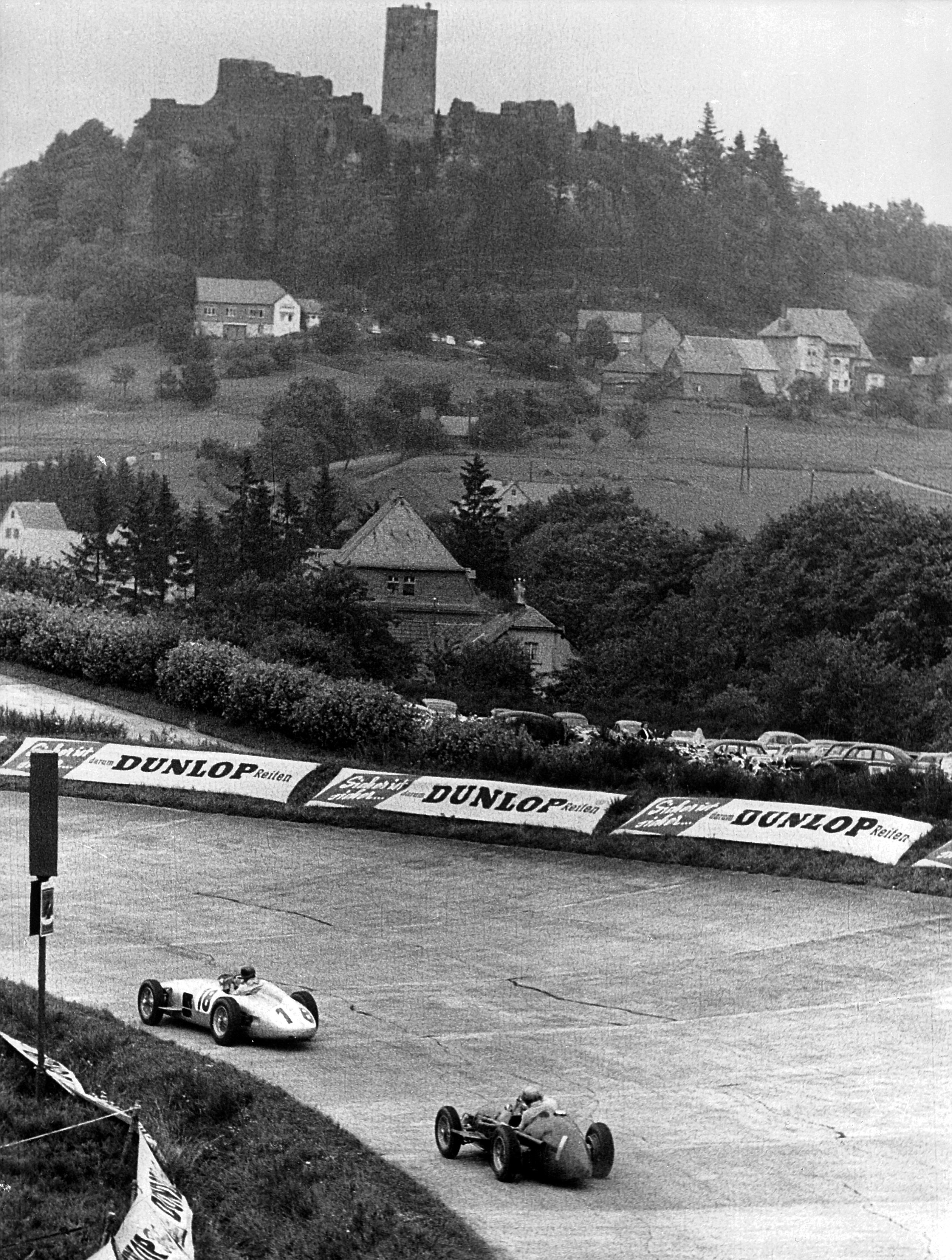

Sunday, 1 August – der Großer Preis von Deutschland: five hundred kilometres, for eight World Championship points.

Fangio and González gave it hell.

The pack of Formula One cars charge off the line – funnel into the South Curve. Accelerating hard, behind the pits – scrabbling for position as they race towards the North Curve, and off into the country.

Gonzáles – Fangio – Moss – Lang – Herrmann. Red and silver blurs. Such a scene – such speed – not seen here in 15 years. Karl Kling – forced to start at the back because of the late arrival of his new W196 – is already making up places. Exploiting the performance and precision of the new Mercedes.

Gonzáles is wringing the Ferrari’s neck on the opening lap. Flugplatz – Fuchsröhre… Fangio is keeping the Ferrari in sight, watching his mirrors for young Moss.

“… I realised that I could not get Marimón out of my mind. I thought of him as sitting by my side and it was as if I could speak to him, saying ‘Now we’ll take that one!’ ‘Now that tricky bend!’ And so, together in memory, we tore down the Adenau slope and at the curve where he had died he was still with me. But I was now myself again, caught up in the irresistible and intoxicating excitement of the race and determined that ‘we’ should win.”

Now, on to the long Döttinger Höhe – a sustained flat-out run, as the road dips and rises.

Gradually the power of the Mercedes begins to reel-in the Ferrari. Rushing towards the end of the straight – the end of the opening lap.

Side-by-side now - watching for the turn to appear at the last second – daring each other to lift first.

Fangio is nerveless.

Gonzáles, aghast; as Fangio mugs him through the kink at Tiergarten, robs him of the lead.

The Silver Arrows will head the field from here to the chequered flag.

“We’ve won, Pinocho,” Fangio murmured as he crossed the line. And as he leapt from the W196 – was slapped on the back by Alfred Neubauer – as the anthem played – as 350,000 people cheered – his ‘racing companion’ departed forever.

The Drivers’ World Championship for 1954 was staged over nine rounds: eight Formula One Grandes Épreuves, and the Indianapolis 500. Unlike the Formula One World Championship of today, each driver’s five best results only would count towards the championship.

Fangio had dominated the season so far. He had won the Argentine and Belgian Grands Prix for Maserati, and the French and German Grands Prix for Mercedes-Benz. One more clear win would secure him the title, but would the W196 be suited to Bremgarten… could Fangio face it, after the loss of Marimon?

Ultimately the answer to both was yes; although neither man nor machine could be taken for granted.

Against a field that lacked Ascari and Villoresi - both awaiting the new Lancia - but facing a strong challenge from González and Moss, Juan Fangio simply raced into the distance. A stunning display of what ‘El Maestro’ and the Silver Arrow could achieve together.

The win at Bremgarten secured for Juan Manuel Fangio his second World Champion Driver title - five wins and two fastest laps making his ‘best five scores’ unsurpassable. Yet it passed with relatively little fanfare, the protagonists having little to say of it in their memoirs.

“I had reached the objective I had set myself at the beginning of the year, but Pinocho’s death still bothered me too much to feel much satisfaction at reaching my goal. At the time of the fatal accident, I had thought I would not race at Berne and eventually took part only because Alfred Neubauer of Mercedes insisted.”

Bremgarten – which had seen so much drama and excitement over two decades, not least between Mercedes and their great rivals – fell silent. No-one present could guess that it was farewell forever.

This first Mercedes-Benz built for Formula One was a triumph and at Bremgarten, for the first time perhaps, winning had looked easy. The win, dominant. The result, a dream. The machine shedding its imperfections with each passing event, through hard work and diligence.

For Mercedes-Benz this was reward for the tireless work at Stuttgart over four years. Fitting too, as it was three years since Neubauer had seen the future in Switzerland: Fangio in dominant full-flight on the Alfetta.

A new beginning, a new formula, a new machine, a new champion – but it was one step on a long road. A road that set out from Paris in 1894.

Next, the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Championship decided perhaps, but the Grandes Épreuves carried great weight and importance. Ferrari and Maserati will do all in their power to avoid a repeat of Reims or Bremgarten. This would be a race for the ages.

With the Lancia Formula One car still not ready to make its debut, Ascari and Villoresi were permitted to start for Ferrari and Maserati, respectively. The pride of Italy was at stake. Pride that took a blow off the start line, as two silver Mercedes streamliners – Fangio from pole, and Kling from fourth – charged into the lead.

Kling - Fangio - Moss, heading the swarm of red cars behind. Then Karl Kling, pushing too hard, dropped the Mercedes at Lesmo. Fangio, alone against the red tide.

Ascari and González, working together, draft past the Mercedes and into the lead. Fangio, keen not to overwork his W196, tucks in. The three cars changing position, back and forth, lap after 110mph lap.

González was first to fall, the Ferrari’s transmission crying ‘enough’. Ascari - Fangio: the two great World Champions nose-to-tail, a two-way scrap. Then it rained, briefly.

Suddenly Villoresi and Moss are back in play, until the Italian’s Maserati breaks its clutch spring and Moss takes the lead - just as Ascari parks the Ferrari with spark plug failure.

Stirling Moss leads from Juan Manuel Fangio, and he’s pulling away from the new champion. Finally, on the biggest stage, with a full works Maserati, Stirling is showing the world what he’s made of.

Neubauer, observing from the pit with concern and interest, orders the signal to Fangio - Moss now has a 20-second lead - PUSH.

Fangio gives the Mercedes its head and presses on, determined to catch young Moss. But not even Fangio is infallible and when the Mercedes gets loose on the marbles he has no choice but let it run wide onto the grass. The machine spins 360 degrees, Fangio deftly catching it and clattering back on to the track. Seconds and speed in the machine lost, Fangio can only watch as Stirling increases his lead.

But, wait… Moss is pitting for oil. Fangio leads, just - but is helplessly watching his mirrors for the inevitable return of Stirling’s Maserati. It never comes.

The oil leak on the Maserati proves terminal, and Moss is forced to stop on the circuit with just a dozen laps to go. The moral winner - if you believe in such things - Stirling pushes the car to the line to the applause of the knowledgeable crowd. They understood the magnitude of the performance, and the disappointment.

Just short of the finish line Stirling stops and leans against the Maserati, exhausted. Legendary photographer Bernard Cahier rushes to buy a bottle of Coca Cola, hands it to Stirling, and takes a famous photograph – a study of disappointment on the edge of greatness.

Fangio crosses the line to win his fourth race of the season for Mercedes-Benz. The other Mercedes are nowhere: Kling failing to finish after an accident, and Herrmann is 4th, three laps behind Fangio’s ailing W196.

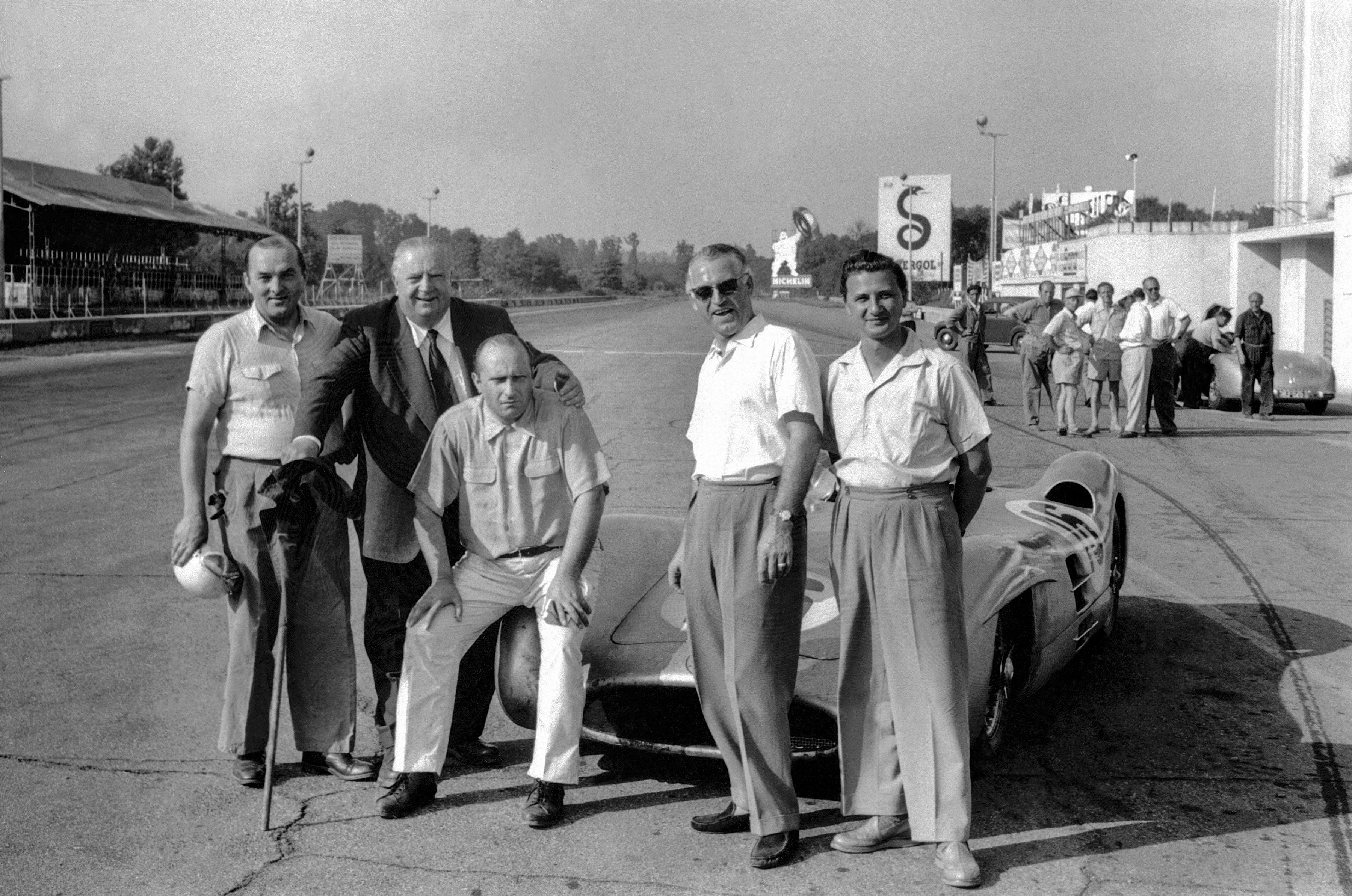

Timing and observation during the race at Monza made clear that cornering was the W196s great weakness. So the team elected to stay on at the circuit to conduct further testing, to explore the issues. Aero testing of the different body types and extensive tyre testing provided excellent information, and provided a clear vision of the required development route for the W196.

Neubauer can see the other weakness, and he knows who he needs in the Mercedes driver roster for 1955.

The final championship race is to be the Spanish Grand Prix, but it is still over six week away. In the meantime the Mercedes-Benz W196 streamliners have a date in Berlin.

The 1954 Berlin Grand Prix was an evocation of the pre-war ‘AVUS Rennen’. In front of some 90,000 spectators, Mercedes lined-up against rather weak opposition for a 60-lap race on the banked speedway at Berlin. It would forever be Mercedes’ only non-championship Formula One race, and win.

Although it would be virtually a demonstration run, it was still a formidable event. In practice Fangio posted a lap at 140.5 mph. The winner, Karl Kling, averaged 132.6 mph over the 60 laps. It was the fastest race run since the war - faster even than the record-breaking Indy 500 of that year.

Demo race or not, the engineers at Untertürkheim learned something every time the cars ran. None of the Mercedes in Berlin had been overstressed, yet Kling’s engine was shown to be down by 20bhp at the finish. On stripping it they found oil and sand in the inlet ports and damaged valves. Air filters are added to the development to-do list.

Mercedes had every reason to believe that they would continue their winning ways at the final championship Formula One race of the season – the Spanish Grand Prix, on the street circuit at Pedralbes, Barcelona. Six cars were brought from Stuttgart and after practice the decision was made to use the open-wheel variant.

Finally, the new Lancia D50 was making its competition debut. A fantastic, innovative Formula One car from the great Vittorio Jano. And what a debut - Ascari putting the new machine on pole position, a second faster than Fangio’s Mercedes.

Ascari and Fangio qualified more than 1.5 seconds faster than the rest. The two champions in a class of their own. The Mercedes of Kling and Herrmann only ninth and 12th on the grid.

Come race day it fell apart for Mercedes – a “debacle”. By the 10th lap the new, fast Lancias were both parked-up, but Mercedes were in no position to benefit.

“While the Mercedes were without question faster than the other machines, they lost in braking all they gained on the straights.”

To make matters worse on such a hot day, discarded newspapers were clogging grilles and blocking radiators. Over-heating was being experienced throughout the field, but the problem was compounded for Mercedes – the airflow to the W196s' inboard brakes was also disrupted.

With an over-heated engine, fuel injection vapour lock, shot brakes and a damaged piston, Fangio limped home in third place - a lap behind race winner Mike Hawthorn. The other Mercedes, all but invisible during the race.

A humbling conclusion to Mercedes’ first Formula One season.

But what a year it had been. Mercedes had produced and developed two variants of a world-beating Formula One car – they had secured the Drivers’ World Championship – but there was much work to do over the winter if the challenge from Lancia, Ferrari and Maserati was to be met.

At Stuttgart they drew a breath, and got back to work.

The New Mercedes

At the Monza test, after the Italian Grand Prix, a new Silver Arrow appeared. 196.110-00001/54 covered 336 miles in testing.

Its body sliced through the air as efficiently as the W196 streamliner. With only 500cc extra it produced more power than the W196, while running on regular gasoline. Box-fresh it lapped Monza at 115 mph.

When asked how this was possible, Uhlenhaut replied, “In six months Mercedes make progress.”

Oh… and it had seating for two.

Meet the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR - “The greatest sports racing car ever built.”

Rudolf Uhlenhaut (right) with the ‘Uhlenhaut’ Coupe, built on the basis of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR (W196 S), 1955

Rudolf Uhlenhaut (right) with the ‘Uhlenhaut’ Coupe, built on the basis of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR (W196 S), 1955

"I don't want the car of today or the car of tomorrow, but the car of the day after tomorrow.”

Emil Jellinek, commissioning the first Mercedes, in 1900